This post covers the invertebrates of the Walking With... series - Walking With Dinosaurs, Beasts, Monsters, and Chased By Sea Monsters, as well as the companion books. There's been a lot of reviews of accuracy and scientific validity of these series over the years but invertebrates are something that get completely ignored in almost every instance.

Some information may be a bit brief as there is not too much to go off of for most of these, but I'm gonna try to say at least something about all the invertebrates featured (with the exception of those in Walking With Cavemen - they're all modern animals meant to represent modern animals, really nothing to say about em).

Starting off with WWD -

Episode one, New Blood only has one invertebrate - a dragonfly, acting as prey for the Peteinosaurus. The narration mentions that bugs of this kind were the uncontested aerial predators for millions of years (the companion book, Walking With Dinosaurs - A Natural History, also mentions Meganeura), which is certainly true - I'll get into that (and Meganeura) once we get into WWM. At this point in the Triassic, true dragonflies had not evolved and would not until the middle Jurassic, but there were crown Anisopterans (Kohli et al. 2021) at this time, so not much of a big deal.

The companion book features many other invertebrates. For brevity's sake I'm just gonna list them off when they appear unless I have something interesting to say about em. New Blood features centipedes, millipedes, camel spiders, whip scorpions and mentions several other groups including grasshoppers and stickbugs. Most interestingly, it features a crayfish, which are well known from the Chinle Formation. Some of the earliest and best preserved fossil crayfish are known from the there, named Enoploclytia porteri in 1988 - Adam Marsh on Twitter has some great pictures of a specimen for those interested

Crayfish burrows are also known from the area, in the ichnogenus/species Camborygma eumekenomos - see Kowalewski et al. 2008 for more info

The

presence of these crayfish, amongst other things, indicates a

swampy/forested area, much more humid and lush than depicted in WWD.

Episode two, Time of the Titans only features two invertebrates, but they're part of something phenomenal - sauropod ecosystems. One can only imagine the bugs that'd live on or around sauropods, not to mention things like dung, in footprints, or even in their eggs. This is something often avoided in media, maybe because it can be a bit gross or disengaging for audiences, which makes sense but ignores a major aspect of sauropod ecology.

We have many internal and external parasites in the Mesozoic fossil record, including but not limited to - osteomyolitis-causing blood worms, various fleas and ticks that may have lived on feathered dinosaurs, and Jurassic blackflies (those poor dinosaurs). There's ample examples of Mesozoic nuisances, so they're certainly not hard to depict, especially as many of the biting bugs could feasibly be portrayed by their modern counterparts.

WWD goes a step further and features animals that would eat those biting bugs, including damselflies.

Damselflies today are essential in wetland environments because they control the numbers of mosquitoes; I can only imagine this was to a much greater extent in the Mesozoic.

These

damselflies use the Diplodocus as giant feeding

platforms. While I couldn't find any mentions of this happening today on something like an elephant or rhino, I

assume this likely does occur somewhere.

And either way, it's a reasonable behavior, the sauropods aren't gonna be able to dissuade them (unless they could, but I doubt we'll ever know).

WWD also portrays dung beetles clearing the Jurassic plains of dung, but this wasn't the case - dung beetles don't appear to have evolved until the early Cretaceous (Gunter et al. 2016).

Instead, it appears that cockroaches would have been doing this job during the Jurassic (and even throughout the Cretaceous - (Vršanský et al. 2013)

This research came out after WWD, and the the assumption that dung beetles were around at the time is by no means unreasonable; beetles started diversifying as early as the Carboniferous.

The companion book features thrips, planthoppers, and more biting flies, but also one incredibly interesting invert - a lacewing with eyespots. This may be inspired by the Kalligrammatids, a Jurassic-early Cretaceous

group of pollinating lacewings that bear a heavy resemblance to butterflies, but they were not predatory. This could also feasibly be some regular lacewing with eyespots.

Here's a phenomenal article on the

Kalligrammatids for those who may want to read more about them - https://palaeoflora.blogspot.com/2022/11/restoring-kalligrammatids-not.html

Cruel Sea actually features a couple different invertebrates, with one actually being important to the story!

In the background there are coral and sponge reefs, which were actually quite prominent during the Jurassic. This all changed in the Cretaceous with the evolution of rudist bivalves, which ultimately went extinct at the end of the Mesozoic, allowing sponges and corals to take over once again. There's also jellyfish on occasion, which are live-acted by modern Aurelia. We actually have several fossil jellyfish from the Jurassic, not closely related to Aurelia as far as I know, but it's certainly a reasonable stand-in.

The

Ophthalmosaurus are depicted feeding on squid, and also interacting with ammonites.

Notably, WWD depicts these ammonites with an operculum (a plate that closes the shell). This was seemingly controversial at the time, but we are now essentially certain they did not have one.

Our uncertainty stems from the previously unknown function of the aptychus, a small bone found in association with ammonites. The aptychus has variously been proposed to be part of an operculum, the jaws, a filter-feeding device, part of the propulsion system, and even male ammonites (Parent and Westermann, 2015).

As our understand of ammonites has improved, we've been able to determine that the aptychus is part of the buccal mass (Tanabe, Kruta, and Landman, 2015).

The ammonites unfortunately do not get much screen time, and wouldn't until Prehistoric Planet (which I'll cover down the line).

Horseshoe crabs, however, do get a bit of time to shine. These horseshoe crabs are live-acted, but this is not an issue by any means as many looked quite close to their extant relatives and some, like the genus Limulus may be as old as the Jurassic. These horseshoe crabs don't do anything too spectacular - it's actually identical to what happens today, even down to the eggs getting fed on by aerial predators.

On land, we briefly see a Rhamphorhynchus trying to get at beetle larvae, the identity of whom may be revealed in the companion book(?). There's a brief mention of a scavenging, insular (?) beetle.

There are fossil beetles known from late Jurassic Europe, in Solnhofen, Germany, but they seem to be primarily water beetles. It seems reasonable to assume something like this existed, but unfortunately there are no fossils. Interesting spec (?) bug though, even if incredibly minor.

Episode four, Giant Of The Skies features three inverts, two of which are bothersome to the other animals. There's biting flies, mentioned earlier, and most interestingly the giant flea Saurophthirus (or a close relative). Saurophthirus was possibly a pterosaur specialist (Gao et al. 2013)!

This flea may have found a host pterosaur, fed on its blood for a bit, and then jumped off into the water to digest, laid its eggs on land somewhere, and then waited for another passing pterosaur to start the cycle over (Rasnitsyn and Strelnikova, 2017).

There's also a very cool pollinating wasp. Pollinators during the early Cretaceous were incredibly varied and unique. There were beetles, kalligrammatids, and a variety of wasps (it seems like bees evolved later). This transitional period has an interesting mix and match of pollinators, as the flora was a lot more evenly split than the angiosperm domination (and bee/butterfly majority) of the latest Cretaceous and Cenozoic (Schatz et al. 2017).

Would love to see this portrayed in other paleomedia; to my knowledge only Life On Our Planet has.

Spirits of the Ice Forest portrays more biting insects (again, those poor dinosaurs!), and best of all - the wētā. The wētā are probably part of a larger Gondwanan lineage, but do not owe their current distribution to this fact, it appears that these bugs dispersed to their current island homes in relatively recent times (Trewick, Wallis, and Morgan-Richards, 2001).

The fact that this bug is used as a stand-in is not that big of a deal, but does sorta give them impression that this bug is a "living fossil" when that is not the case. The specific species used is Hemideina maori, the mountain stone wētā - this bug is quite unique for its freeze tolerance. There are a lot of interesting cellular adaptations that allow for this to occur -

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022191097000188?via%3Dihub

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s003600050215

Death of a Dynasty features a single invertebrate, the last one of the series, in an incredibly minor role via some stock footage - butterflies. Butterflies appear to have first evolved in the middle Cretaceous and diversified heavily in North America by the time of the KPG, as shown by two recent papers led by Akito Kawahara -

https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1907847116

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-023-02041-9

These late Mesozoic butterflies would've ushered in the floral/pollinator communities of the Cenozoic, as they were probably incredibly efficient pollinators.

The book mentions ostracods and sand fleas, but those don't do much.

WWD features many invertebrates - they do not tend to get major parts, but they're present, which really aids in fleshing the worlds out drastically. Walking With Beasts does not follow up on this, unfortunately.

Starting off with New Dawn, most are nothing more than prey for the Leptictidium; there's a damselfly and cricket (which turns into an ant lol). Most prominently, there's the giant ant Titanomyrma gigantea (formerly Formicium giganteum). Titanomyrma is a European/North American genus of giant ant - T. gigantea is the largest ant of all time. Fossil queens measure 2.8 inches, with a wingspan of over 6 inches. Males on the other hand grew about an inch long; we have no fossils from workers.

Most of the fossils of T. gigantea seem to be flying females, likely because these individuals drowned during mating swarms. Unfortunately, there has been no research done of their diet and their social structure is up in the air; the behavior presented in Walking With Beasts is plausible. The episode uses footage of modern Eciton and Formica as stand-ins.

Whale Killer features one invert on screen - fiddler crabs, unsure of the species.

These guys should not be here - fiddler crabs evolved in the Miocene (Gibert et al. 2013).

The narration mentions parasites, which Walking With Beasts - A Prehistoric Safari, the companion book, confirms to be lice and barnacles. I'm unable to find any studies giving a date of evolution for Whale lice (Cyamidae) - they maybe have evolved in the Eocene or later, on larger baleen whales. Whale barnacles (Coronulidae) are known from the time, though- the genus Emersonius is known from Eocene deposits in Florida (Chan et al. 2021).

The book also mentions Nummulites - shelled planktonic organisms which collected on the seafloor in large numbers. The female Basilosaurus rubs against these to scrape the parasites off her body.

The other four episodes - Land of Giants, Next of Kin, Sabre Tooth, and Mammoth Journey - all feature flies in the background, but nothing specific to go off of, resulting in a dissapointing lack of inverts.

Walking With Monsters makes up for this immensely - by virtue of being a Paleozoic documentary, features a lot of invertebrates. It was the big debut for many of the popular ones like Arthropluera and Anomalocaris, but unfortunately it hasn’t aged too well.

Starting with Water Dwellers, the first segment (that features animals) of this episode takes place in Cambrian China, using some of the Chengjiang Biota, which is a phenomenal assemblage of animals that rivals the Burgess Shale in terms of diversity and preservation. This segment takes place at the wrong time – the segment is set 530 million years ago, while the Chengjiang fauna are only 518 million years old.

The first invertebrates we see are jellyfish, some sort of Scyphozoan (jellyfish are not my specialty). Scyphozoans first appeared during the Fortunian (roughly 538 to 529 mya), so their presence here is certainly justified (Liu et al. 2017).

We then see some trilobites; these are supposedly Redlichia based on what I've read, but they're not

named in the show. Redlichia is a genus of trilobite known from across the

globe. This genus doesn’t appear to have been a part of the Chengjiang Biota,

but a former species (now Eoredlichia) was, so it gets a pass. Only issue is the lack of antennae.

The “Anomalocaris” is where big issues start to crop up. First off, this species is now two genera - Innovatiocaris and Houcaris. Due to the historically fragmentary nature of radiodonts many different remains were described initially as Anomalocaris, only recent research has started to fix this. Some of these have stuck while others have turned out to belong to entirely different groups of animals - the idea that Anomalocaris could grow six feet long stems from an early description of what would later be named Omnidens (Chen, Ramsköld, Zhou, 1994). The largest genuine Anomalocaris, A. canadensis, only got maybe three feet long.

Houcaris is just a pair front appendages, so we can’t guess body shape nor size, but it probably would not have been big either. Innovatiocaris is only a few inches long. Most of this taxonomic information was published long after WWM aired, so it’s not at fault. Other recent research has shown that portraying “Anomalocaris” as a trilobite eater is inaccurate.

This was long assumed to be true, but studies in recent years have found

that the oral cones and front appendages of these radiodonts were not equipped to process armored

food. They likely would’ve ate worms or jellyfish instead, via suction (Daley and Bergström, 2012), (Bicknell et al. 2023).

Bite marks on trilobites attributed to Anomalocaris seem to belong to Peytoia,

while coprolites with trilobite fragments seemingly belong to other trilobites (Daley et al. 2013). Even so, Anomalocaris was still an apex predator - that 2023 study found that Anomalocaris was an active, efficient predator, swimming with its appendages outstretched. This is quite contrary to what the narration states, claiming that armored animals are rigid and slow (look at mantes and tell me they're slow).

The narration also states that about 80% of animals in the area have armor. I

haven’t sat down and calculated a number, but I do think that is wrong.

First, that’d depend on what you count as “armor” – do you count the

skeleton of sponges, for example. Secondly, preservation bias certainly

plays a factor. Although

these sites preserve a phenomenal diversity of soft-bodied and

hard-bodied invertebrates, they do not preserve everything, I’m almost

certain that animals like jellyfish, worms, and Isoxyids were much more

prevalent in these ecosystems than we currently realize.

Anomalocaris

also wouldn’t be part of that “armored” group, the radiodonts were

soft-bodied, except for the head, which was protected by a carapace.

Unfortunately, other interesting

Cambrian animals like Hallucigenia aren’t shown, but that was likely due

to budget - this sequence is a remarkably inoffensive portrayal of Cambrian life, especially for the time.

Moving on to the Silurian; this sequence technically takes place during

the earliest Devonian, it’s another instance of WWM fucking up times. WWM

has a lot of time travelers; there’s some Diadema urchins, which first

appeared in the Jurassic. There’s also an Endocerid orthocone, all of

which went extinct during the Ordovician. The

urchins are somewhat reasonable background animals, but still funny to

see. Shoehorning in an orthocone is interesting, especially because it

doesn’t do anything. I'll touch on the issues with this model later on, though.

Before getting to the main scorpion, I want to briefly talk about Pterygotus. Pterygotus

is not the largest arthropod, that honor belongs to Jaekelopterus.

Jaekelopterus was originally described as a species of Pterygotus, but

given a new genus in 1964 based on some differences which later proved

to be untrue. Even

so, there were many other traits that separated the two genera, and

they remain distinct – I want to believe that WWM meant that Pterygotus

was the largest arthropod to live at that point, but that’s probably not

what was intended.

Brontoscorpio is apparently only known from a pedipalp (front pincer), so very little is known about it.

Despite how it's often portrayed (and even something that I pedaled in my initial thread), there is not reason to suggest Brontoscorpio was entirely aquatic - the single pedipalp was found in terrestrial deposits after all. There would have been bustling terrestrial communities of small invertebrates for these scorpions to eat. Furthermore, earlier scorpions possessed tarsi that were used for terrestrial locomotion (Waddington, Rudkin, and Dunlop, 2015), so there's no reason why Brontoscorpio wouldn't have the physical capability to move on land either. The argument that it was too big to support itself on land falls through when things like Pulmonoscorpius and Praearcturus (which may be synonymous with Brontoscorpio) exist.

Another issue with this segment is the statement that arthropods have no memory – arthropods react to and remember queues, both positive and negative, and they have great spacial awareness and recognition - https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-319-47829-6_830-1

We don’t have much on stem-arthropod brains, but it seems feasible that

these traits would have been present. If WWM can depict a eurypterid with parental care, there's no reason to suggest that inverts do not have memories.

Water Dwellers features on more (live-acted) scorpion. There have been fragments of scorpions from the Red Hill site, but they’ve not been described as far as I know - https://web.archive.org/web/20210711205338/http://www.devoniantimes.org/who/pages/otherInverts.html

Water Dwellers introduces a lot of interesting invertebrates, but certainly not enough – the brevity of the episode (and series) is truly unfortunate. Episode 2, Reptile’s Beginnings, features the last major hoorah of the invertebrates – the late Carboniferous/early Permian.

Interestingly, the Carboniferous segment

takes place (300mya) after the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse (~305mya),

inadvertently combating the misconception that these bugs died out around this

time (the largest Arthropleura and several griffinflies are from the early

Permian; the latter even made it to the Great Dying). This is due to WWM just generalizing time though, especially

because it repeats the idea that the giant Carboniferous bugs were only

possible because of the higher oxygen levels. Although high oxygen levels may have aided at least some of the large insects, faunal interactions

were the main driver, and have been through all insect evolution, as shown by

trends during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic -

https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1204026109

https://chooser.crossref.org/?doi=10.1144%2Fjgs2021-115

https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/JIGE/article/view/JIGE0808120115A/32759

The lack of flying vertebrates seems to have allowed invertebrates to fill the

niche of aerial predator (remember when WWD said dragonflies went uncontested for millions of years?), with increases in size being caused by prey availability, and maybe even

an “arms race” between the Palaeodictyopterans and griffinflies (Liu et al. 2015).

Speaking

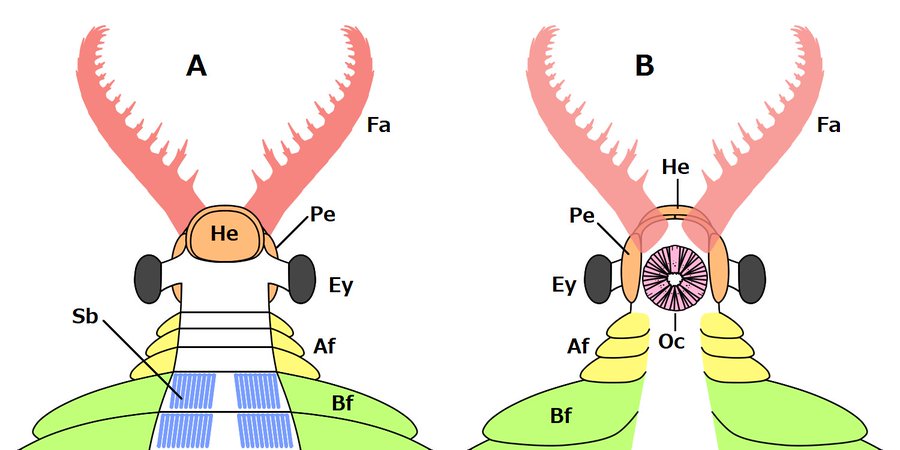

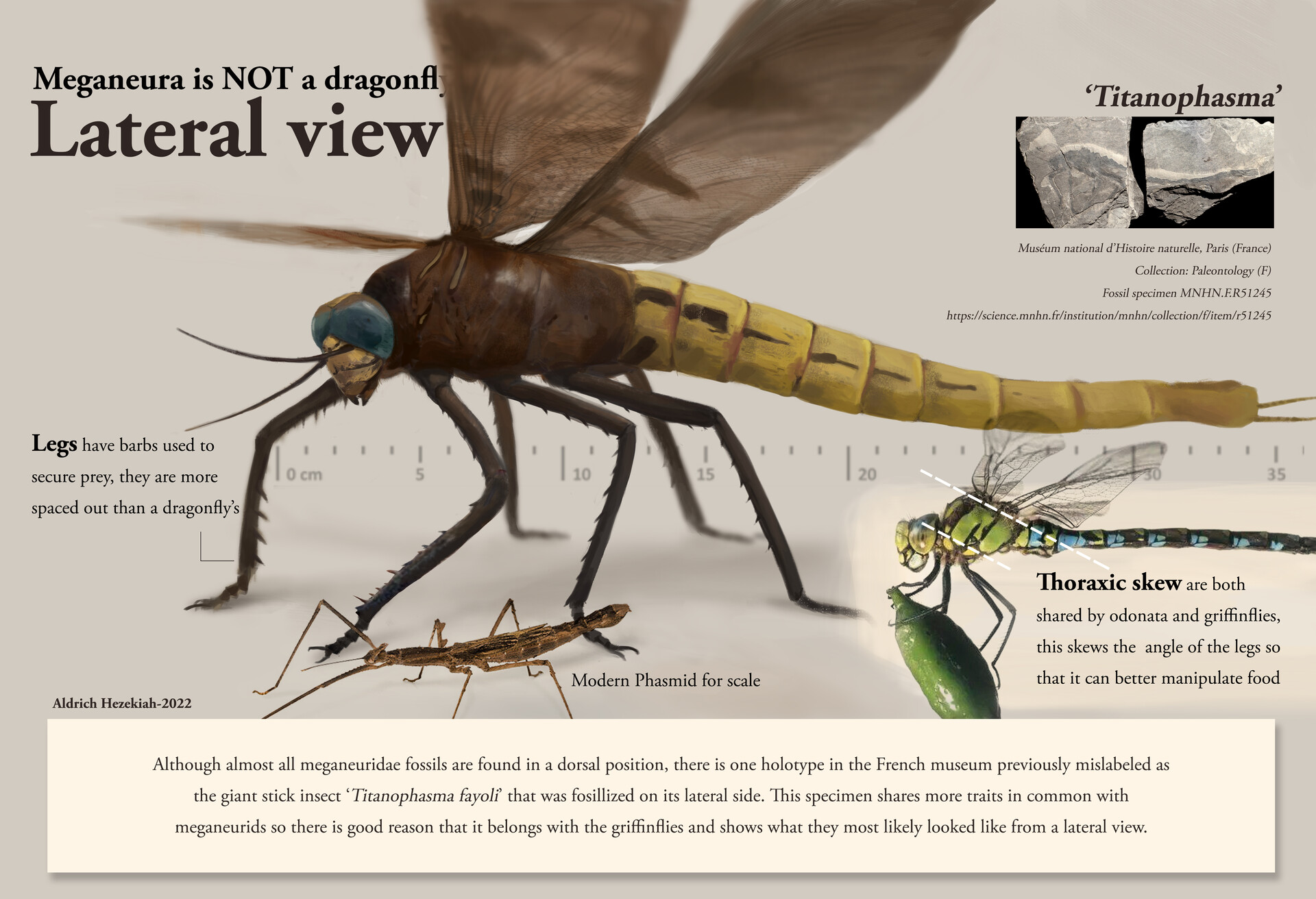

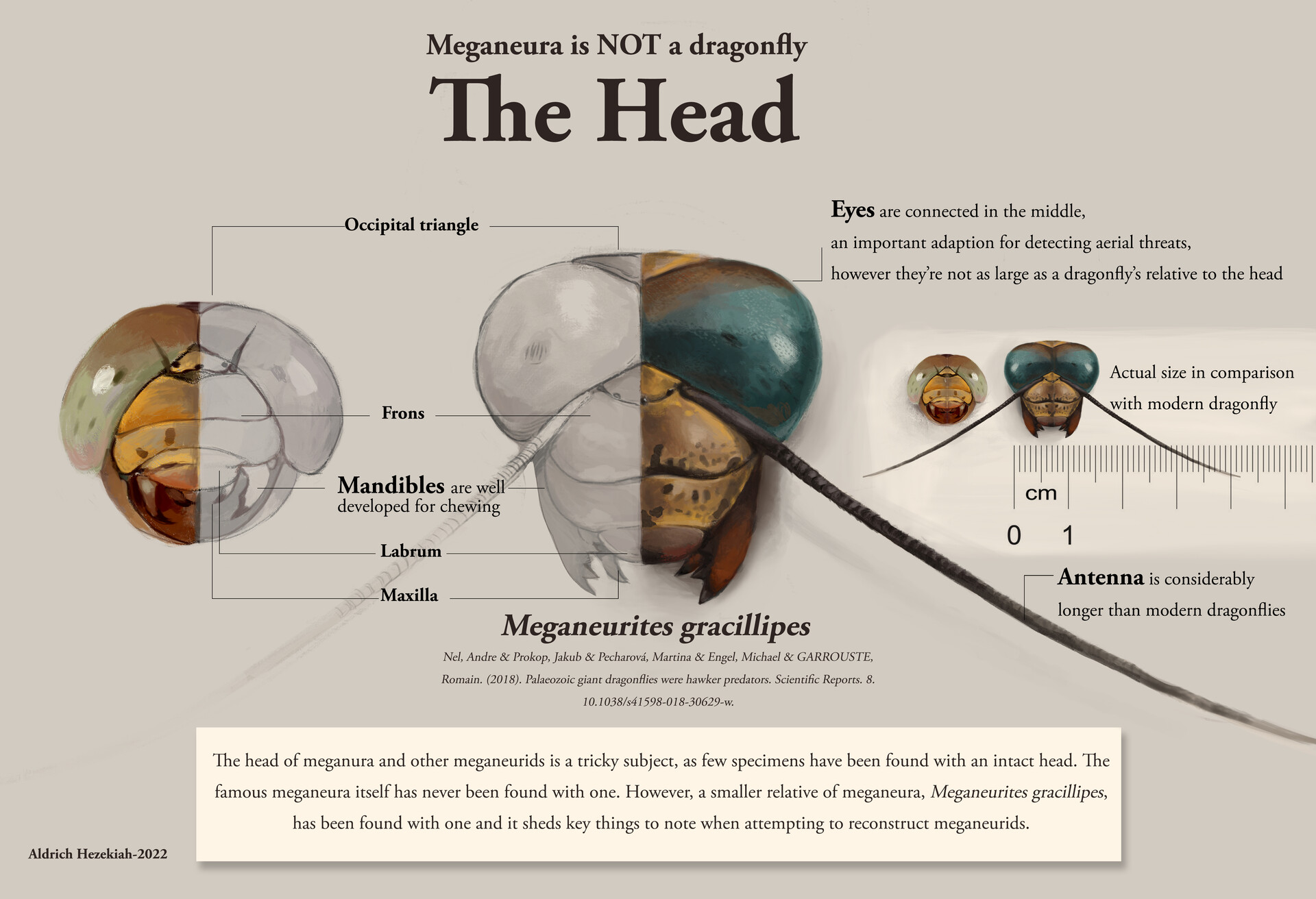

of griffinflies, they were not just giant dragonflies! They were fairly

distinct and quite unique. These pieces by Aldrich Hezekiah (@aldrich_kia)

explain it better than I can, and are really well done regardless.

As

for the other bugs featured, there’s a few sorta iffy things about

Arthropleura. We have yet to find Arthopleura jaws, so the centipede-

like reconstruction is entirely speculative, and a bit exaggerated, at

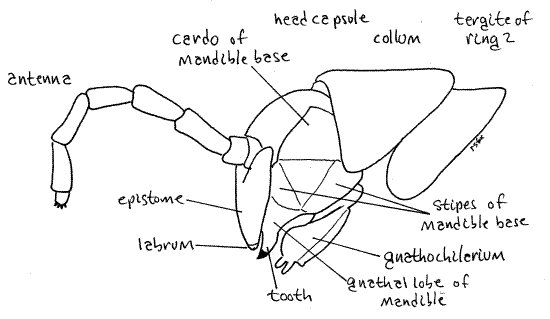

least in my opinion. In general, the model gives it a centipede-esque head and completely lacks the collum (segment before the head), which is preserved in fossils

This image is a modern Pachydesmus for comparison -

Also we have no idea whether it could rear up or not. I don’t think it’s

impossible, but it’s much more likely they just curled into a ball. Maybe if the Arthropleura did that, it wouldn't have died.

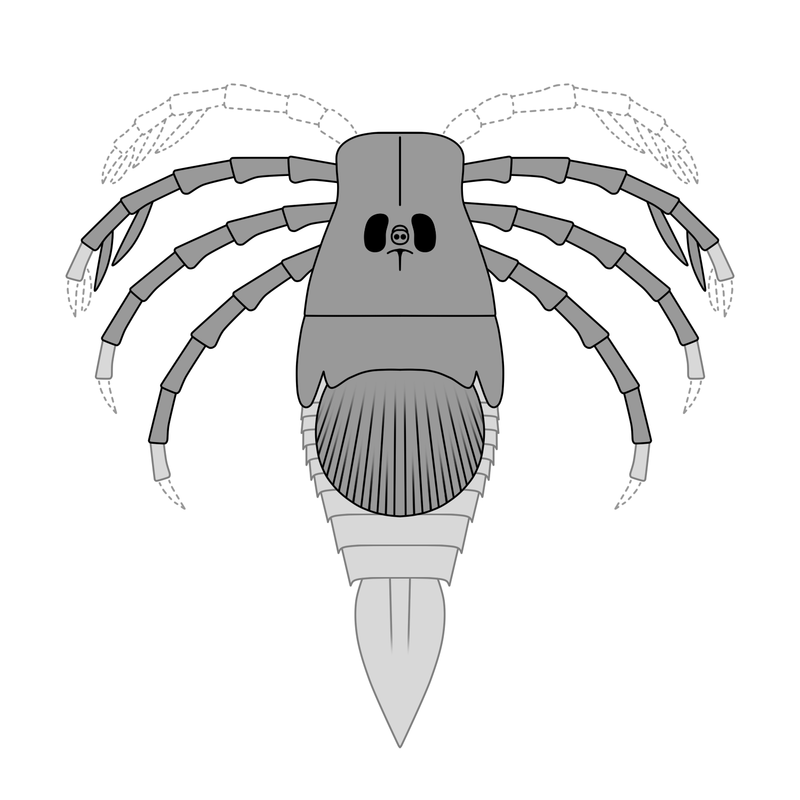

The main offender of this episode is "Mesothelae", based on Megarachne,

which was originally proposed to be a giant spider, now known to be a

Mycteropoid eurypterid.

This information came out too late in WWM's production for correction, so the identity of this bug became "Mesothelae", which is not a genus (as commonly assumed), but refers to a suborder of spiders. Mesothelae spiders do date back to the Carboniferous, and are pretty well represented by fossils, but look pretty different from WWM's spider - https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12542-023-00657-7

The

WWM Mesothelae takes heavy behavioral inspiration from funnel web

spiders (Atracidae), maybe expanding on the "trapdoor" behaviors of the related, extant Liphistiidae, which is certainly reasonable.

I do find it interesting that WWM states that these spiders cannot

burrow and must steal from others, when this is not the case in any trapdoor spider today; if this spider consistently lived in burrows, it'd figure out how to make em. But, for an essentially made up animal, WWM's giant spider is pretty reasonable!

Episode

three just features some "dragonflies"; nothing too offensive if you

pretend they aren't true dragonflies. Overall WWM features some

incredibly interesting invertebrates, I only wish there were more of em.

Chased

by Sea Monsters sorta scratches that itch - it features my favorite

fossil invertebrate (which unfortunately isn't too great), and has some

phenomenal depictions of two others.

These invertebrates appear in the 7th deadliest ocean, the Ordovician. This time period doesn’t get featured very often, and although the star of this sequence has aged quite poorly, representation is still representation. The sequence features three invertebrates – Isotelus, Megalograptus, and Endoceras, inspired by the Cincinnati Arch, an area renowned for its fossils from this time.

The

Isotelus looks pretty good, but it’s also nothing more than a dead

specimen unfortunately. Once again, there's a lack of antennae but that's the only issue. Isotleus rex was the largest trilobite known at the

time (that honor now belongs to Hungioides bohemicus), which is probably why this genus was featured.

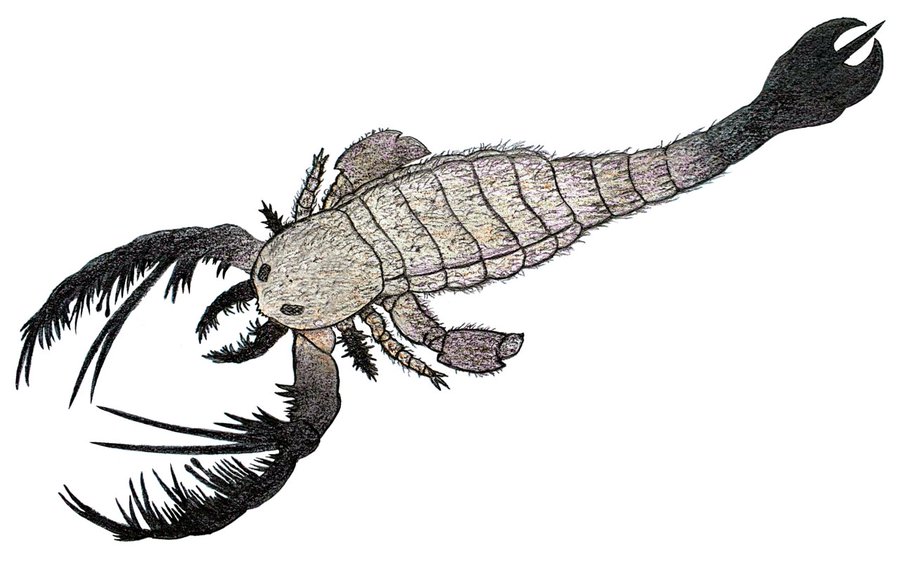

The

Megalograptus is also, actually, incredibly good! I didn’t notice

anything wrong with its anatomy, nor behavior! I’m assuming, based on

the colors, that this is M. shideleri.

This

may seem like an odd and unfounded assumption, but there’s actual

(seemingly good) evidence of color in not just one, but three species of

Megalograptus (and also another eurypterid, Carcinosoma)! The

1964 description of three species – M. ohioensis, M. shideleri, and M.

williamsae reported that, based on the composition of incredibly

well-preserved specimens, mineralization did not occur or had been

lessened, so the color of the fossil specimens had not been lost or distorted - https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/10693962#page/398/mode/1up

M.

shiedeleri was a mix of different shades of brown and a hint of black,

while M. ohioensis was mostly dark brown and black; M. williamsae had a

similar, but lighter, color scheme.

This image is M. ohioensis

The

diet of the Megalograptus is all based on fossil evidence too!

Coprolites found around a specimen of M. ohioensis contained scraps of

Isotleus, and other eurypterid coprolites from Ohio contain the remains

of jawless fish (Selden, 1984).

We do know Eurypterids could move on land based on tracks; recent ones have been found from this time period in New York (Braddy and Gass, 2023). Mass spawning and moulting is also supported based on comparative anatomy and fossil evidence - (Vrazo and Braddy, 2011).

While the Megalograptus and Isotelus are so good, the Endoceras (Cameroceras) hasn't withstood the test of time at all.

Starting off with the few things it gets right - it's in the right time and place, has pinhole-type eyes and adhesive ridges on the arms (both of which are inferred ancestral conditions of cephalopods based on phylogenetic bracketing). The Endoceras correctly has a nautilus-like operculum (based on fossil evidence), and a benthic, predatory lifestyle feeding on Eurypterids. It gets the general nautiloid-esque appearance down, at least (and doesn't lean too hard into that, like Prehistoric Assassins does).

By the way, I'm referencing @TylerGreenfieId's wonderful guide to reconstructing the genus Endoceras - incertaesedisblog.wordpress.com/2020/02/16/rec, sources for everything presented can be found within.

The Sea Monsters model has eight arms, although imprints showing that orthocones had ten have been known since 1955. Mentions of truck-size orthocones (such as in Walking With Monsters) are pretty flawed; the supposed 30 foot specimen has not been verified. The operculum seems small and useless, when it should be large enough to seal the body into the shell, while the shell itself is perfectly straight when it should be slightly curved at the end. The orientation of the Endoceras is seemingly its biggest offense - a 2019 paper used 3-D modelling to determine the swimming orientation and stability of several Paleozoic cephalopods, and found that orthocones moved vertically.

Finally, these are Endoceras, not Cameroceras! Cameroceras was historically a wastebasket taxa with shaky nature of early descriptions led to a variety of orthocone species being put under this name, something that is only now getting sorted out. Endoceras has been used to refer to better-preserved sizeable orthocones since the 1950's, something backed up by modern research - https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267268188

As far as I can tell, the largest currently accepted species of Cameroceras is about 6 feet; still sizeable, but not as big as Endoceras.

It's a shame that this depiction didn't age so well, especially because of how magical it is, but I'm certain there's more to come in the future. Life On Our Planet gives a good idea of the behavior of these guys.

That's essentially it for Walking With...! I'm slowly going through The Complete Guide To Prehistoric Life and have yet to amend this post with inclusions from the Chased By Sea Monsters companion book, but all the major stuff has been covered! Unsure what I'll do next, probably Life On Our Planet or Prehistoric Park.

Images –

Anomalocaris swimming – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anomalocaris#/media/File:Anomalocaris_ecological.png

Anomalocaris carapace - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radiodonta#/media/File:20190908_Radiodonta_Anomalocaris_Anterior.png

Brontoscorpio - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brontoscorpio#/media/File:20210123_Brontoscorpio_anglicus_size_estimation.png

Pachydesmus anatomy - https://lanwebs.lander.edu/faculty/rsfox/invertebrates/pachydesmus.html

Megarachne - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Megarachne#/media/File:20210116_Megarachne_hypothetical_reconstruction.png

Megalograptus - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Megalograptus#/media/File:Megalograptus_color_reconstruction.png

No comments:

Post a Comment